CAGE - What can it do for you?

- Highly sensitive and accurate quantitative transcriptome analysis not only as a gene, but as a Transcription Start Site (TSS).

- Reliable way to discover Transcription Factor binding motif based on the true TSS nearby the actual promoter.

- Unique and powerful tool to discover alternative promoters for all endogenous genes.

- Help you to discover new biomarker and/or bidirectional enhancer RNA.

- Clarifying the heterogeneity and complexity of transcriptomes from the view of Cause of Transcription instead of expression profiling.

- Linking expression values to promoter sites for a better understanding of how signaling pathways regulate transcription.

- PCR-free operation procedures provide unbiased quantification of transcript amount.

Difference from RNA-Seq and other gene expression analysis techniques

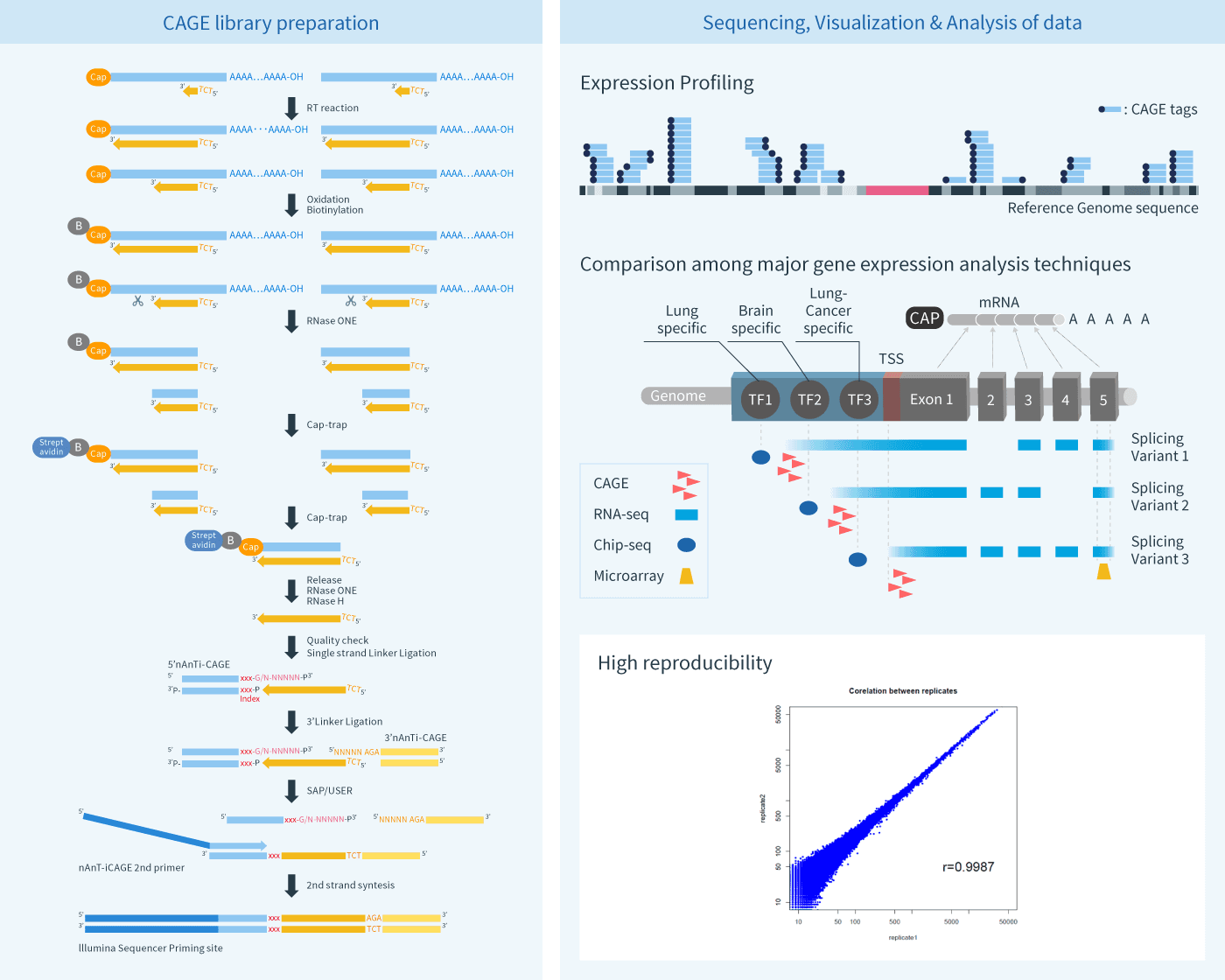

Different from Microarray and RNA-seq, CAGE is able to accurately identify transcriptional start sites (TSSs) and the corresponding promoter regions through sequencing the 3’ end of cDNA (5’ end of RNA). This makes CAGE a powerful tool to analyze the gene regulation in the TSSs level, enabling analysis of the gene regulated by multiple alternative promoters. Therefore, CAGE can serve as a new perspective approach for genome annotation, by elucidating transcriptional signaling cascades, and performing other functions.

| CAGE | RNA-seq | SAGE | Microarray | |

| de novo Gene Finding | good | good | good | N/A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Quantification | superior*1 1 *1 free of PCR bias unaffected by gene size |

good | good | average |

| Determining Promoter Site | superior | average | N/A | N/A |

| Motif Finding for Transcription Factor Binding Site | superior | average | average*2 2 *2 depending on known 5' end sequence information |

average*3 2 *3 depending on known 5' end sequence information |

| Identification of Bidirectional Enhancer RNA | superior | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Determining Transcription Start/1st Exon Site | superior | average | N/A | N/A |

| Determining Gene Structure (intron/exon, alternative splicing variants) | N/A | average*43 *4 depending on sequence depth |

N/A | N/A |

| Duration of Work Process | average | average | average | good |

| Library Preparation Complicatedness | Long Time 4 (8 days) | average | average | easy |

| Data Analysis Tools | average | good | average | good |

("N/A" means not applicable)

- 1 free of PCR bias and unaffected by gene size

- 2 depending on known 5' end sequence information

- 3 depending on sequence depth

- 4 8 days

What is the CAGE method?

Cap Analysis of Gene Expression (CAGE) is a method for promoter identification and transcription profiling developed by RIKEN (Patent Number: US 6174669, US 6221599, US8809518, etc.). CAGE utilizes a “cap-trapping” technology based on the biotinylation of the 7-methylguanosine cap of Pol II transcripts, to pull down the 5’-complete cDNAs reversely transcribed from the captured transcripts. Through a massive parallel sequencing of the 5’ end of cDNA and analysis of the sequenced tags, transcription start sites and transcripts amount are inferred on a genome-wide scale. Thus, CAGE provides an effective genome-wide transcriptional profiling as an alternative to microarray and RNA-seq.

We are offering CAGE library preparation service with or without sequencing & basic bioinformatics analysis.

| Specification | Comment | |

| Total RNA required | 3 μg of total RNA/sample for PCR free CAGE library | If possible, please provide 12μg of total RNA for PCR free CAGE library preparation service. CAGE library can be prepared from few 100ng of total RNA, by adding PCR amplification. |

|---|---|---|

| RNA entry QC | Bioanalyzer | We perform entry QC on all samples. |

| DNA amount of CAGE library | Several ng | DNA fragments ready for Illumina NGS sequencer. |

| Sequencing platform | Illumina NextSeq 500/2000 | |

| Number of reads per sample guaranteed | 15M reads/sample | |

| Additional reads are available with additional charge | Number of lanes per sample | |

| Mapping rate | About 75% of tags map to unique mapping position | 4 M mappable CAGE tags / sample is guaranteed. |

| Sequence data | Provided with Illumina file format | Delimited text files holding sequence information and quality scores. |

| Data Analysis | Mapping positions, Read count quantification, CTSS clustering, Differential expression analysis, Gene Ontology enrichment analysis and Transcriptional Factor binding motif search | Tables/flat files: number of raw reads, number of extracted tags, number of mapped tags, etc. |

Learn More About the Analysis Methodology

See details about sequencing, visualization, and analysis of data.