CAGE-seqの利点

- 各遺伝子を転写開始点ごとに定量:世界で唯一、ゲノムワイドにプロモーター活性を定量解析できる技術

- 定量性に優れる:PCRの工程が無く、5’末端に特化してシークエンスするため、RNA-seqのように長さのバイアスも無く、定量性に優れる

- 高感度:200万のRNA分子から1つのRNAを99.99%の確度で検出可能

- 新規RNA分子(mRNA、lncRNAやエンハンサーRNAなどのncRNA)・プロモーターを発見できる可能性もある

- 転写因子結合モチーフ探索:発現変動が確認された転写開始点周辺情報を基に、モチーフ配列を探索することで、関与していた可能性のある転写因子を予測することができます

- 大規模、かつ、高速の解析が低コストで実現可能

- 理研とダナフォームが共同開発した技術

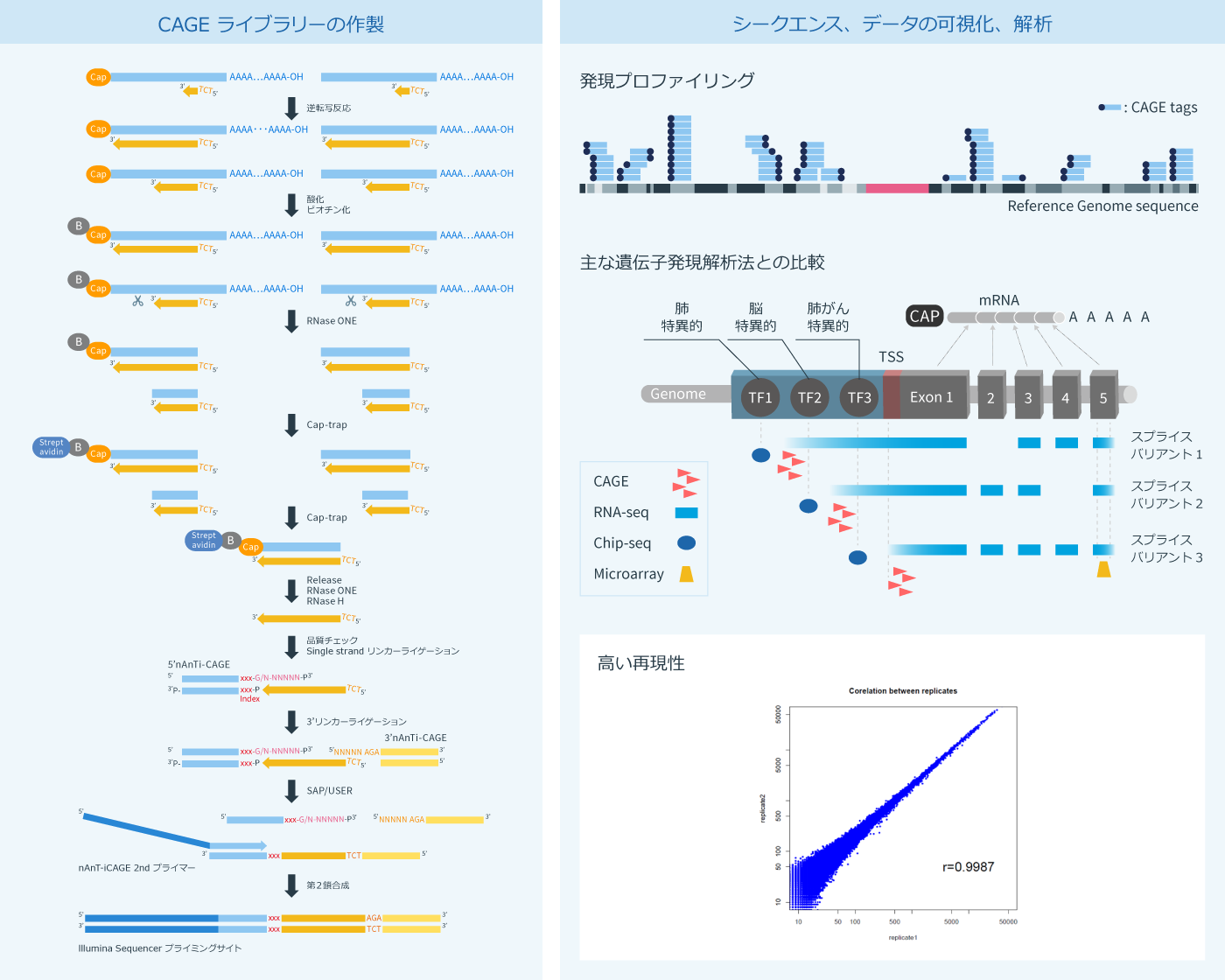

RNA-seqやその他の発現解析技術との比較

遺伝子発現解析の手法は多くあり、それぞれに利点があります。 CAGE-seqが他の遺伝子発現解析手法とは異なる最大のポイントは、CAGE-seqがゲノムワイドに転写開始点を正確に同定できる点にあります。

CAGE-seqでは、プロモーター領域の詳細な解析ができるため、特定遺伝子の発現制御に関与したプロモーターごとに分けて解析することが可能となり、転写のシグナル伝達のカスケードを明らかにするなど、新しい視点に立ったゲノムアノテーションが可能になります。

ダナフォームではCAGE受託解析をお引き受けしています。

| CAGE-seq | RNA-seq | SAGE | マイクロアレイ | |

| 未知遺伝子を含むトランスクリプトーム解析 | ○ | ○ | ○ | x |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 定量性/ダイナミックレンジ | ◎ ※1 | ○ | ○ | △ |

| プロモーター部位の同定 | ◎ | △ | x | x |

| Transcription Factor Binding Motifの予測 | ◎ | △ | x ※2 | x ※2 |

| Bidirectional enhancer RNAの同定 | ◎ | x | x | x |

| Alternative Exon1の同定 | ◎ | △ | x | x |

| 選択的スプライシングや融合転写物など遺伝子の構造の同定 | x | △ ※3 | x | x |

| 全工程にかかる解析所要期間 | △ | △ ※3 | △ | ○ |

| サンプル調整難易度 | × ※4 | △ | △ | ◎ |

| データ解析ツール | △ | ○ | △ | ○ |

- ※1 PCR工程も無く、長さのバイアスも無い

- ※2 5'末端はデータベース情報に依存

- ※3 Sequence depthによる

- ※4 8日間の工程

CAGE-seqとは?

CAGE-seqは、理化学研究所にて開発されたRNAseqやマイクロアレイに代わる新しい発現解析方法で、完全長のcDNAのみを回収し、mRNAやlncRNAの発現量および転写開始点(Transcription starting site)を網羅的に解析する方法です。その特徴は、RNAの5’末端に付加されるキャップ構造を特異的にビオチン化して回収するところにあります(Cap-trap法)。PCRによる増幅工程をライブラリー作製過程から完全に排除することにより、CAGE-seqは、他の方法よりも定量性に優れ、広いダイナミックレンジを有しています。さらに、転写因子結合モチーフやalternative promoterの探索、高度な遺伝子制御ネットワークの推定など、CAGE-seqの結果からは多くの情報を得ることができます。

データの解析方法についての詳細

シークエンス、データの可視化、解析についての詳細はこちら

サンプルデータダウンロード

未処理のFASTQ形式データ、処理済みのFASTQ形式データ、参照用ゲノム、解析結果をダウンロードする

* ファイルサイズが32.6GBになるためダウンロードに時間がかかります。

ダウンロード